Open the closet, but don't come out

How Kádár's suppression still shapes LGBTQ rights in Hungary

Recently, someone asked me about LGBTQ rights in Hungary, specifically whether it is safe to be an LGBTQ person in Hungary, with all this anti-LGBTQ propaganda going on.

I’m not an expert on LGBTQ rights; my knowledge in this area is limited. However, I do know some cultural and historical aspects of the broader sociological context. It can be traced back to the socialist era under the regime of János Kádár. Let’s discuss the 3T.

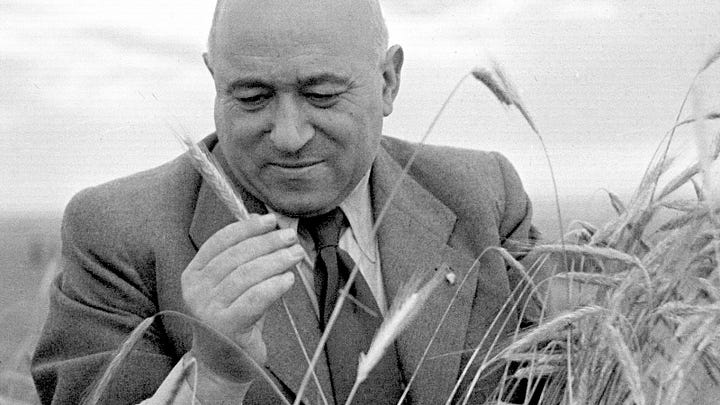

Any regime trying to use direct oppression against Hungarians will face a revolution. After the 1956 revolution, the newly installed dictator, János Kádár, learned from the mistakes of Mátyás Rákosi, the previous communist dictator. The difference between them is usually described by their respective political creeds. Rákosi’s one was “If someone is not with us, they are against us,” while Kádár’s dictum was: “If someone is not against us, they are with us.”

By the early 1960s, the political trials against the 1956 revolutionaries were over. Many people opted to leave the country at the first opportunity. For others, the regime offered a modus vivendi, a way of peaceful coexistence. This is not unique to Hungary. Every other European communist country had something like this but to a varied extent. Hungary was the most liberal in this respect, hence the moniker “the happiest barrack of the camp.”

However, this relative freedom came at a price. While the regime did not actively suppress individuals, they expected self-suppression. This system was known as the “3T system” in the cultural sphere.

The 3T stands for:

Tiltott - Prohibited

Tűrt - Tolerated

Támogatott - Supported

Writers, artists, theater and film directors, poets, and musicians were expected to know where the regime’s tolerance ended. However, there was no clear line to define that limit. Different tolerance standards were applied in television, theater, or private settings. A Hungarian artist was expected to know the subtle difference between saying something about the regime in a small, semi-legal theatre or saying (in fact, not saying or not like that) the same for a wider audience.

Even giving a vague set of criteria of that fine line is difficult. But probably the best way to describe it is that whatever the criticism was, it had to be ineffective. Saying it too loudly, directly, or for too many people crossed the line.

Kádár’s omnipresent network of informers, operated by the infamous 3/3 department of the Interior Ministry, ensured that the appropriate authorities heard any transgressions. My first boss shared a story about how, during a private meeting with around 15 people, he criticized the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. He was a high school senior back then, a hot-headed 18-year-old. The following day, he was summoned to meet with the county’s Party secretary, received a stern warning, and then faced a five-year wait to gain admission to law school despite having good grades. One of the attendees at that meeting was an informer.

This system caused more damage than any violence could. A whole society learned to control itself, question itself, and always stay safely a step behind that line. It was just a step, but any wise person kept that distance.

No oppression is more efficient than self-oppression

The impact of this subtle self-oppression is still with us. Since 2010, most opposition parties have existed in the 2nd T-category. Orbán allows them to exist, but if they grow too big, “something happens” to them. The authorities raid the offices, or they receive a fine, that sort of thing. The “Sovereignty Protection Office” is the most recent addition to the harassment toolkit.

Being in the 2nd T-tier also means you can be subjected to harassment at any time just to make you feel that what you do is not entirely okay. It is still tolerated, but don’t you dare think your actions are right. It isn’t; you color outside the line, but the regime lets you do that. But don’t take that for granted. Know your place.

This system has existed long enough to develop its behavioral patterns, both internally and externally. Internally, individuals learn to act cautiously and to question their actions. Externally, the expectations placed on tolerated groups become established standards. Adhering to these standards provides a sense of security and makes it easier to live close to the “line.”

What does this have to do with LGBTQ rights?

LGBTQ individuals have always existed in every society. The real question is whether they can come out of the closet. Being openly gay, marrying a same-sex partner, and having an LGBTQ scene in Budapest—or anywhere else in Hungary —was labeled with the first “T” (prohibited).

In certain places, such as some steam baths and specific clubs, the regime subtly accepted gay culture. Code words like the English term “confirmed bachelor” were often used to refer to men of a particular sexual orientation. It was tacitly understood that a certain pianist or film director might have an “apprentice” or a “close friend.” This situation resembled the atmosphere of Victorian Britain.

This meant that to a certain level, with a lot of caveats, being semi-openly gay was tolerated. But that certain level was not high, and the door on the closet could only be opened slightly. Coming out of the closet was out of the question—the “solidified expectations” described above required being mindful that not being straight was not okay.

It also meant that LGBTQ people who followed the expectations were tolerated but with a level of commiseration. “Yeah, the poor chap is gay, but otherwise, he is such a nice guy and tries to go discreetly about this.” This was the best-case scenario.

This atmosphere was suffocating because of the constant fear of stepping over that “line.” LGBTQ individuals learned to be highly cautious when expressing their sexual orientation. Those in lower tiers of society often faced blackmail, a tool to make them informers. Places of freedom were scarce, and they were closely monitored.

The semi-closeted lifestyle led to a situation where most Hungarians still know very little about LGBTQ people. Misconceptions (of sexual nature) still have a following. Many people also believe that someone can be turned gay by early indoctrination. Mixing homosexuality with pedophilia is also common.

That leaves us with a society that has been trained for three decades about how “decent” LGBTQ people should behave and how “indecent” LGBTQ individuals attempt to disrupt our peaceful community.

Homophobia? Maybe not.

A surprisingly high number of Hungarians are accepting of homosexuality. Living in a very prudish society, they consider it a topic best left undiscussed. The “decent” behavior is to be discreet about it like it was a “problem.”

However, they often have a problem with LGBTQ people leaving their assigned lots within society, i.e., to live a free, open, and happy life. This is where government propaganda kicks in. Many people have limited knowledge about LGBTQ life and the issues faced by the community. As a result, they tend to believe the propaganda that claims certain “indecent” gay individuals—those who reject the second “T” label and seek true freedom—want to turn children gay to increase their numbers and all the other nonsense.

Determining how much anti-gay sentiment stems from actual homophobia versus resentment towards those who strive to find happiness in an unhappy society is quite hard to say. But one thing is for sure: if things start to go south, anti-LGBTQ propaganda is fired up almost instantly.

(Grammarly wanted me to correct the passive voice in this article. I dismissed most of the suggested corrections. The passive voice shows the indirect way the 3T system shaped the Hungarian society.)

Thank you for reading and following the Muse!

If you like our articles, please consider becoming a paid subscriber! Right now, my Hungarian blog is the main cash cow, but I plan to allocate more resources towards this one to serve my paid subscribers with better and more frequent content.

I want the Muse to be interactive. Do you live in Hungary? Have you heard any news about Hungary? If you have questions, please ask them in the comments or email them to me directly by clicking this button:

“While the regime did not actively suppress individuals…” oh yes it did, when someone didn't _know their place_ .

But for those who had nothing against the system and could fit in well, it indeed felt like no suppression

There was a film titled "Egymásra nézve" ("Another Way"), which premiered in 1982, six years before Kádár's downfall in 1988. Unfortunately, I am not familiar with the film's production history, but I remember that an exceptionally large number of people watched it at the time (including myself) and it later achieved cultfilm status thanks to e.g. its overt depiction of lesbian sexuality too. (Kultfilm/Cultfilm=these films typically possess a unique, quirky, or non-traditional style that makes them stand out from other films and eventually achieve cult status over time.).